|

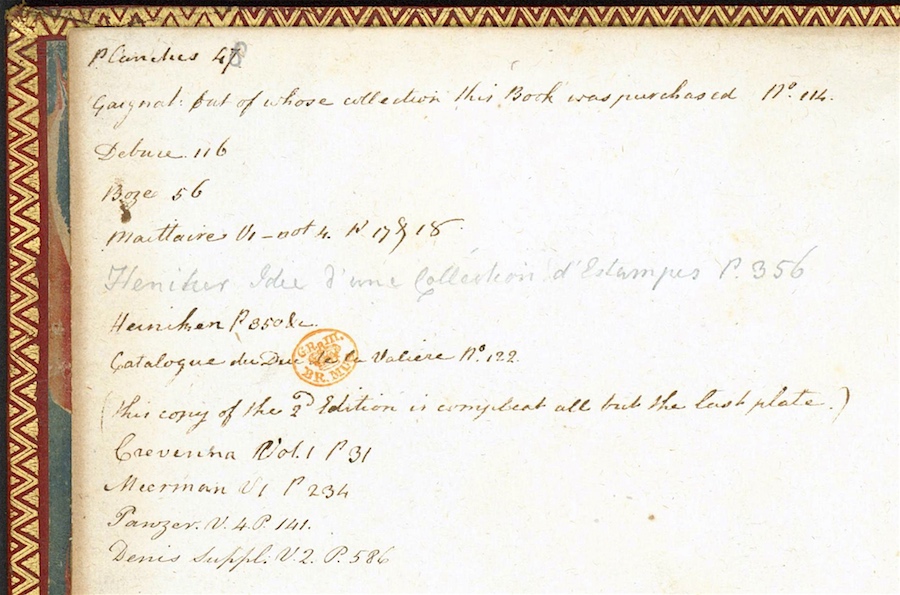

On the previous page we were trying to track down the title of a spectacular binding in the the British Library Database of Bookbindings shelfmarked C9c1, owned by King George III and said to have come the library of Gaignat. It seemed likely that it would be found in de Bures catalogue of Gaignats books assembled for the 1769 auction of them after Gaignat's death in 1768. However finding it in that catalogue was no small task without the correct title. The title given by the British Library for C9c1 was so strange that you needed to be a clairvoyant to imagine what it was. I wanted to find out how this binding and that of the Speculum currently in the Library of Congress could be identical, who had them bound by Derome le Jeune and more importantly when? Fortunately Philippa Marks has found a list on one of the blank pages in C9c1 (shown above) the second item on this list tells us exactly what we have been searching for. The first item in this list is what appears to be "Planches 47" with the 7 replaced with an 8, after this we see "Gaignat: out of whose collection this book was purchased, No. 114." This is number 114 in De Bures 1769 auction catalogue, below I have reproduced a rough translation of the catalogue text as well as a copy of the catalogue pages where number 114 is found... |

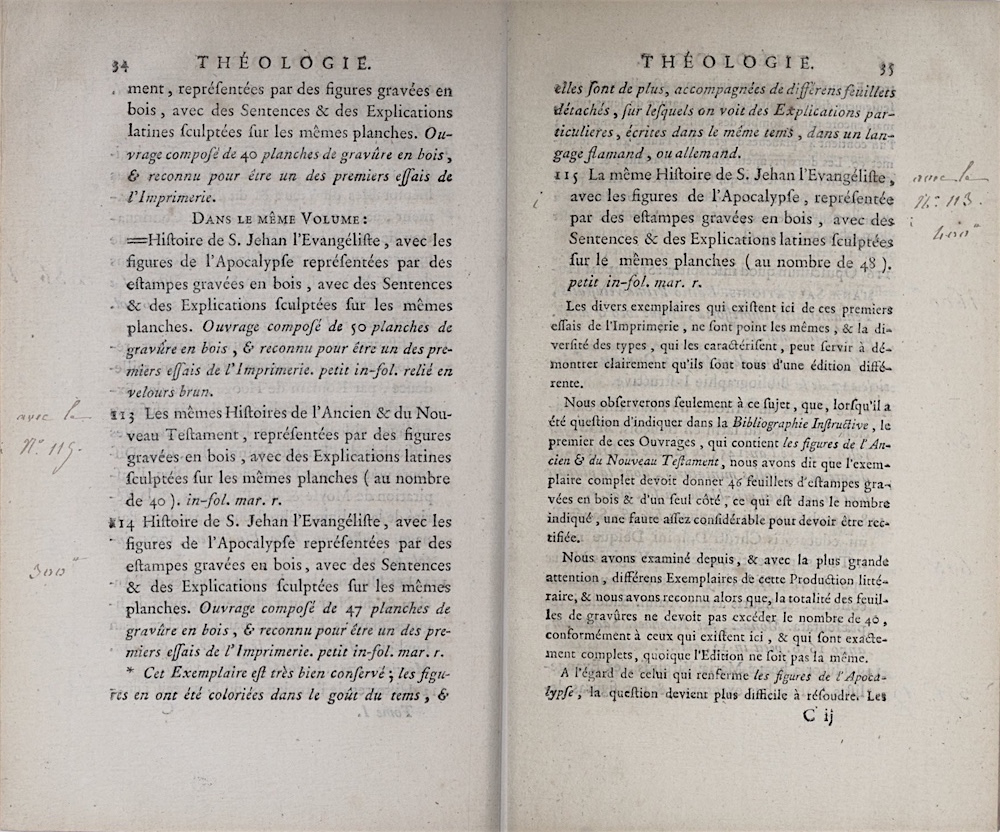

| 114 - History of St. Jehan 1'Evangeliste, with figures of the apocalypse engraved on wooden boards, accompanied with sentences and explanations carved on the same boards. this work consists of 47 boards of wood engraving, and is recognized to be one of the earliest forms of printing. small in fol. maroquin rouge. this copy is very well preserved; the figures have been colored in the taste of the time, also accompanied by different detached sheets, on which we see particular explications, written in the same time, in a Flemish language, or German. |

| I had looked at this item 114 and 113 before thinking that they could possibly be what I was looking for however one could not be sure without more information. The next item on this list is "Debure 116" this is a reference to De Bures main catalogue entry for this same book, it is found in Volume 1 of Bibliographie instructive: ou, Traite de la connoissance des livres rares et singuliers... Par Guillaume-Francois De Bure, le jeune..., below, I show a rough translation of the text as well as a copy of the actual catalogue page |

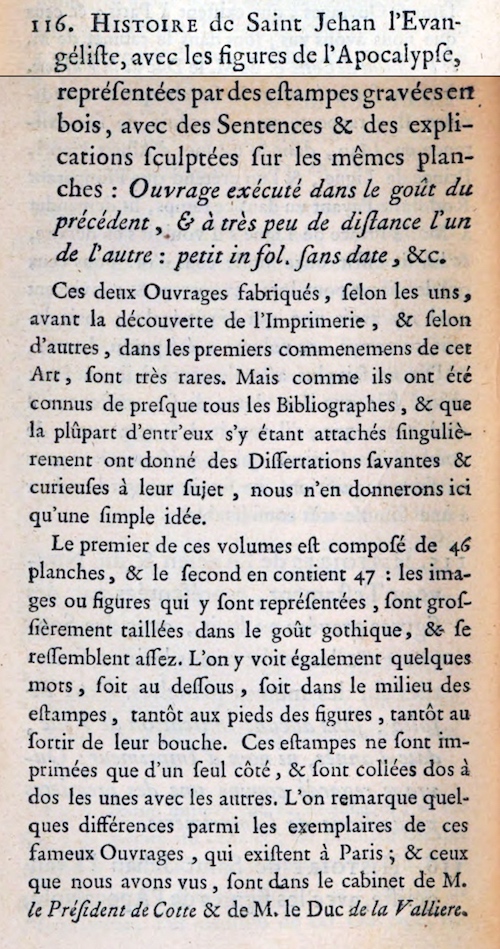

| 116. HISTORY of Saint Jehan the Evangelist, with figures of the Apocalypse, represented by engravings in wood, with sentences & explanations carved on the same boards: Work executed in the taste of the previous (115) and very similar to each other: small folio. no date, etc. These two works manufactured, according to some, before the discovery of printing, and according to others, in the first beginnings of this art. They are very rare, but as they have been known to almost all the Bibliographers, and since most of them have attached themselves to them singularly, they have given us some curious dissertations about them, we shall give here only a brief description. The first of these volumes is composed of 46 plates, and the second contains 47: the images or figures which are represented, are roughly carved in Gothic taste, and are quite similar. We also see some words, either below or in the middle of prints, sometimes at the feet of figures, sometimes out of their mouths. These prints are printed on one side only, and are glued back to back with each other. There are some differences among the copies of these famous works, which exist in Paris; and those that we have seen are in the cabinet of the President of Cotte and the Duc de la Valliere. |

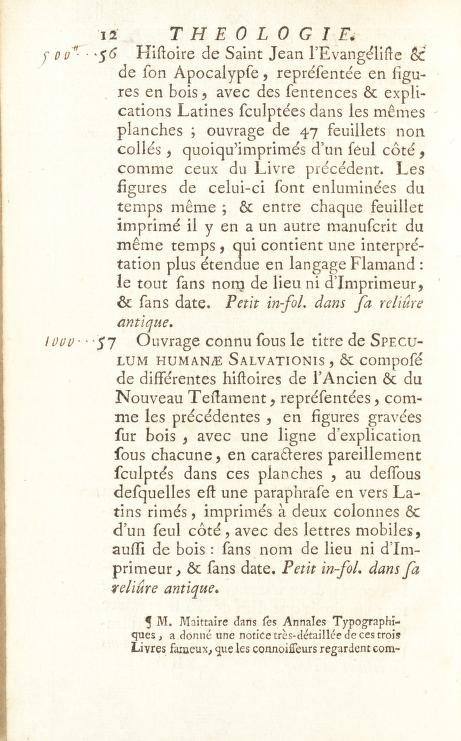

| The next name on this list is "Boze 56" this is a reference to the 1745 catalogue of Claude Gros de Boze (1680-1753). Christies was selling one recently (click here to see it) from this we learn something about this catalogue... |

| THE NOTORIOUSLY RARE LIBRARY CATALOGUE of the De Boze collection, privately published in an edition limited to a few dozen copies (the number is variously given as 25, 36 and 90) for distribution to friends of the collector. De Boze was a distinguished numismatist, who as a young man had worked for the King on Medailles du regne de Louis le Grand (1702). He was secretary of the Academie des Inscriptions for thirty-seven years, published the first fifteen volumes of the Academy's Memoires, collaborated on its official history, and was elected to Fenelon's seat at the Academie francaise in 1715. He was one of the most important book collectors under Louis XV, owning copies of the Gutenberg Bible (acquired after 1745), both Mainz Psalters, blockbooks, a long series of editiones principes, and several Grolier bindings. Although Boudot wrote this private catalogue, he was not entrusted with the sale of the collection after De Boze died, the task going to Gabriel Martin. |

|

Finding item 56 in the catalogue of Boze was an easy task as it can be found at archive.org (click here to see it) here we discover something fantastic!... the Speculum is listed right under 56... turning now to the Bodlleian information on the Speculum we find it. |

| Provenance: de Wandermark (early eighteenth century); see Jean-Baptiste Michel Papillon, Traite historique et pratique de la gravure en bois, 2 vols (Paris, 1766), I 104. Claude Gros de Boze (1680-1753); given to de Boze by de Wandermark, for which see Papillon I 104; see also Catalogue des livres du cabinet de M. de Boze (Paris, 1753), I no. 57; Guillaume de Bure, Bibliographie instructive ou traite de la connaissance des livres rares et singuliers, 8 vols (Paris, 1763-8), vol. de theologie (1763), p. 128. President de Cotte (eighteenth century); see Papillon I 104. Louis Jean de Gaignat (1697-1768); see Guillaume de Bure, Bibliographie instructive: Supplement, 2 vols (Paris, 1769), lot 116; sold for 1600 francs to Girardot de Prefond. Paul Girardot de Prefond ( after c.1800); item rebound for him; on the front pastedown a small label of red leather inscribed in gold: 'Ex musaeo Pauli Girardot de Prefond'. Justin, comte MacCarthy Reagh (1744-1811); sale (1815), lot 142, sold for 1320 francs. George Hibbert (1757-1837); sale (1829), lot 7588; purchased by Douce; see Munby, Connoisseurs, 54. Francis Douce (1757-1834); armorial book-plate. Bequeathed in 1834 [provenances ex informatione Nigel F. Palmer and Roger Middleton]. |

| Now I was lucky to follow up the notes in Christies auction for the next item at the auction was another Boze catalogue with even more pertinent information (click here to see it) we are on a lucky roll here as we have uncovered the whole history... |

| CLAUDE-CESAR TEYSSIER'S COPY OF MARTIN'S DE BOZE CATALOGUE, which confirms and extends what is known about the circumstances and outcome of the sale before the auction. It contains in Teyssier's hand three sets of manuscript prices next to the lot entries: Gabriel Martin's sale estimates, Guillaume-Francois Debure's estimates where they differed, and the prices realized of those books that were resold by Martin on behalf of MM. Boutin and Cotte, who had bought the library en-bloc. Thus, for example, lot 806, Guillaume Bude's copy of the 1488 Florentine editio princeps of Homer, was estimated at 600 livres by Martin, 300 livres by Debure, but was knocked down at 175 livres a year later. However, such comparisons must be made with caution because, as the anonymous author of the manuscript Note sur le present catalogue (inserted after the title) points out, Boutin and Cotte occasionally substituted their own copy of an edition if De Boze's was superior. Martin's and Debure's valuations, carried out at Teyssier's instruction, had only differed by 640 livres, the higher being 123,072 livres. However, Teyssier agreed to sell the collection en-bloc before the scheduled auction for 83,000 livres, to Jules-Franois de Cotte, President au Parlement de Paris, and Charles-Robert Boutin, Maitre des Requetes. The buyers kept for themselves what they wanted, sold much of the finest early printing to Gaignat, recouping most of their cost, and turned the balance back over to Martin for auction the following year. Taylor p. 233; North 104. |

| It would seem that this is how these books wound up in Gaignats library, this connects to the Heinecken reference Idee generale d'une collection complete d'estampes by Karl Heinrich von Heinecken page 356, shown below, it tells of the book having been sold to the King however there is no mention of the binding. Heinecken was so interested in counting the actual number of plates in this edition, that he failed to note anything about the binding. Normally there are 48 plates in this book however one is missing which explains the "planche 47" note. |

|

Next we look at the reference to Catalogue du Duc de la Viliere No. 122, this is a reference to a 1783 De Bure catalogue that is also found on archive.org (click here to see it)

Catalogue des livres de la bibliothque de feu M. le duc de la Vallire

by La Valliere, Louis Cesar de La Baume Le Blanc, duc de, 1708-1780; Debure, Guillaume, 1734-1820. I show below the relevent pages for No. 122 as well as 123 which is the Speculum. This is again the work of De Bure fairly much as it was in his1769 Gaignat catalogue however you will notice a few important details have changed, the title is now Historia Sancti Johannis Evangelistae, Ejusque Visiones Apocalypticae and there is finally a mention of dentelles. |

| The next one was a lot harder to find as I was not sure of the spelling, really it took hours, trying to find all these references, but by going back and fourth between them and testing every possibility of spelling I finally found, Maittaire, Michael, 1668-1747, v.1 1719 Annales typographici ... Opera (click here to see it). Trying to decipher the page number was another problem, finally I decided on Maittaire V1 - not 4 p. 17 & 18. but this was only after I landed on page 17 simply by chance, then started reading from the beginning of the catalogue, not easy because it is in Latin, however by this time I was so tired that Latin was looking like French and I thought I was reading it. Then I thought I would try to search for the word 'apocalypse' in the text and that didn't work (needed a latin spelling) but by that time I was back on page 17 where I first landed by chance and I saw what looked like 'apocalypse' at the top of the page and said to myself hey maybe this is it, went back to look at the reference numbers which then magically looked like '17&18 and here we are, maybe the pages shown below are the reference. You can see in the text a lot of words that connect, at the bottom of page 17 you see part of the title Sancti Joannis Evangilistae on page 18 we find in the second paragraph Speculum Humanae above that I see in the first paragraph visions ejus Apocalypticae so this must be it! |

|

When I searched Google with the "Historia Sancti Johannis Evangelistae, Ejusque Visiones Apocalypticae" title, I found an 1803 book by Thomas Astle The origin and progress of writing, as well hieroglyphic as elementary ... this lead me to the name Pietro Antonio Bolongaro Crevenna, which when searched takes you to an Oxford reference so you know you are on the right track (click here to see it ) also I found that the bookseller Jonathan Hill was selling his catalogue (click here to see this) This is lucky as the spelling of this in the list isn't so obvious. IA British Library reference helped me to find an online copy of this catalogue Catalogue raisonne de la collection de livres de m. Pierre Antoine Bolongaro Crevenna, Volume 1 By Pietro Antonio Bolongaro Crevenna (click here to see it). The Crevenna, Vol. 1 P. 31 reference takes you to a page where you find the name Meerman, this name is also not so obvious in the list, I searched a long time for Mercman, and was glad to finally find the right spelling |

| Mercman (V. 1 P. 234) Origines typographicae by Meerman, Gerard, 1722-1771a copy of this is found on archive.org (click here to see it) below I show page 234 as well as the Panzer reference. |

| Panzer V.4.P 141 Panzer Annales typographici ab artis inventae origine ad annvm MD, Panzer, Georg Wolfgang Franz, 1729-1805 |

|

The following notes come from the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica article Typography (click here to see it) Xylo-chirographs. of which written texts were added to pictures printed from wooden blocks; in others the text was written first, and woodcuts pasted or printed in spaces reserved for them. These books, combining wood-engraving with handwriting, are now in technical language called xylo-chirographs (wood-handwritten books); they may also be called semi-block books, and form an intervening stage between the manuscript book and the blockbook (xylograph) entirely printed from wooden blocks. They tend to show that xylography, after having been for some time confined to the production and multiplication of insulated pictures, was gradually applied to the printing of whole series of illustrations, to be added to written texts, or to have written texts added to them. It is not possible to assign definite dates to these xylo-chirographs; they could hardly be placed after, but may, for ought we know, be contemporaries of the blockbooks. We know nine of them; the years 1440 (which occurs in No. 5) and 1463 (found in No. 9) marking, for the present, the period within which they can be placed. (1) Biblia Pauperum, in the Heidelberg University Library, German work, MS., Latin text added to engravings (cf. Schreiber, Manuel, iv. 90, c. 1460; photogr. pl. xlv.); (2) Anti-christus, one part of which is in the Paris Bibl. St Gen. (see Bernard, Orig. de l'impr. i. 102), another at Vienna, Alb. Bibl.; Bavarian work, MS., German text added to engravings (Schreiber iv. 231, pl. lv.); (3) Vita et Passio Jesu Christi, 48 leaves, in the Vienna Hofbibliothek, German work, the woodcuts printed on the versos, Latin prayers written on the rectos (Schreiber iv. 321, c. 1450, pl. lxxxx.); (4) Septem planetae, seven xylographically printed plates in the Berlin K. K. Library, German work, with German explanatory text written on separate leaves facing the engravings (Schreiber iv. 417, c. 1470, pl. cxi.); (5) Pomerium spirituale, by Henricus de Pomerio (or Henri Vanden Bogaert), in the Brussels Royal Library, bearing the date 1440 in two places; its twelve engravings seem to have originally been published as a block book, without any text (see below);[8] in this copy they are cut up, pasted on other (contemporary) leaves of paper, and a Latin MS. commentary added to them (see Alvin, Documents iconogr.; Schreiber iv. 317, pl. lxiv.; Conway, Notes on the Exercitium super Pater Noster; Holtrop, Mon. typ. p. 9). Some bibliographers unreasonably contend that the engravings cannot be earlier than c. 1470, and that the year 1440 is the date of the original, now lost, which the transcriber of this copy inadvertently repeated. (6) Exercitium super Pater Noster (ascribed for good reasons to the same Henri Vanden Bogaert); imperfect copy (8 leaves) in the Paris National Library (Invent. D. 1581); woodcuts printed on the recto of each leaf, and an explanatory text (in Flemish) written underneath them (Schreiber iv. 245, pl. lxxxvii.; Conway, l. c.); (7) the same Exercitium, with the same eleven engravings that were issued, some time before, as a complete blockbook (see below), a copy of which is preserved in the public library at Mons, in which the engravings are cut up and (after the Flemish verses of the blockbook had been cut away) pasted, with their versos, on the versos of other contemporary leaves, with an explanatory (Latin) text written on the recto of the leaf next to each engraving (Schreiber iv. 247, pl. lxxxviii.; Conway, l. c.; (8) a MS. of the Speculum humanae salvationis, with the written date 1461 (Munich Hof.-u. Staatsbibl. cod. lat. 21543), in which the 192 illustrations, usually found in the MSS. of the Speculum, have been impressed from small wooden blocks in the spaces reserved for them in the MS.; (9) another MS. of a German version of the Speculum in the same Munich library (Cod. Ger. 1126), with the written date 1463, in which the 192 woodcut illustrations, impressed in No. 8, are again impressed in the spaces reserved, for them. Of blockbooks of probable German origin the following are known: Blockbooks of German Origin. 1. The Apocalypsis, or Historia S. Johannis evangelistae ejusque visiones apocalypticae (Germ. Das Buch der haymlichen Offenbarungen Sanct Johans.) Of this work six or seven editions are said to exist, each containing 48 (the 2nd and 3rd edition 50) illustrations, on as many anopisthographic leaves, which seem to have been divided into three quires of eight sheets each. The first edition alone is without signatures. Cf. S. L. Sotheby, The Blockbooks, i. 1. A copy of the 5th edition (according to W. L. Schreiber, Manuel, iv. 168), 48 leaves, is in the Cambridge University Library. A copy of the supposed 4th edition in the British Museum (C. 9, c. 1), and one of the 6th edition (IB. 14); The Costeriana. Xylographic Printing. Of the Speculum humanae salvationis, a folio Latin blockbook (that is, an edition printed entirely from wooden blocks) must have been printed several years before 1471, consisting, like the later type-printed Latin editions, of at least 32 sheets = 64 leaves, all printed on one side of the leaf only, alternately on the versos or rectos (therefore 64 printed pages). The sheets were, no doubt, arranged in the same number of quires (a3 for the preface; bcd7, e8 = 29 sheets for the text) as in the later editions; the first leaf was perhaps blank, the preface occupied the leaves 2 to 6, and 58 leaves remained for the 29 chapters of text, each occupying two opposite pages of two columns each. We may further assume that the upper part of each printed page of the text was occupied by one of the woodcuts, which we know from the later editions, and which are divided each into two compartments or scenes by a pillar, with a line or legend below each compartment explaining, in Latin, the subject of the engraving; and that underneath the woodcut was the text, in two columns, corresponding to the two divisions of the engraving above. This blockbook has already been alluded to above among the Netherlandish blockbooks, but we give here further details, as various circumstances make it clear that it was the work of the same (Haarlem) printer who issued the other editions of the Speculum, together with the several incunabula described below, and to whom a Haarlem tradition ascribes the invention of printing. All the Speculum editions which concern us contain, so far as we know, 29 chapters. But previous to the above blockbook another one of more than 29 chapters (may be 45, like most of the MSS.) must have existed, as may be inferred from Johan Veldener's 4to edition of a Dutch version of the Speculum, published in 1483, in which all the 58 blocks of the old folio editions reappear cut up into 116 halves to suit this smaller edition, besides twelve additional woodcuts for three additional chapters (the 25th, 28th and 29th) not found in any of the old folio editions. As these additional woodcuts appear to be also cut-up halves of six larger blocks, they point to the existence, at some earlier period, of a folio edition (xylochirographic or xylographic?) of at least 32 chapters, at present unknown to us. Of the blockbook as is here assumed we know now only 10 sheets or 20 leaves, which, in combination with 22 sheets or 44 typographically printed leaves, make up an edition, called, on account of this mixture of xylography and typography, the mixed Latin edition. These twenty xylographic leaves are (counting the 6 leaves of the type-printed preface) 7 + 20, 8 + 19, 10 + 17, 11 + 16, 12 + 15, 13 + 14 (in quire b); 22 + 33, 23 + 32, 27 + 28 (in quire c); 52 + 61 (in quire e). Copies of this mixed Latin edition still existing: (1) Bodleian Library, Oxford (Douce collection, 205) perfect; (2 and 3) Paris National Library, 2 copies, one perfect, the other wanting the first (blank) leaf; (4) John Rylands Library at Manchester (Spencer collection), wanting the first (blank) leaf; (5) Colonel Geo. Lindsay Holford, London, wanting the first (blank) leaf; (6) British Museum (Grenville collection), wanting the leaves 1 (blank) and 21 (this being supplied in facsimile); (7) Royal Public Library at Hanover, wanting the leaves 19 (xylogr.) and 24 (typ.), but having duplicates of the (xylogr.) leaves 15 and 28; (8) Museum Meerman- Westreenen, |

|

I did not find exactly the Denis Suppl. V2 P 586 reference unless it is Johann Nepomuk Cosmas Michael Denis, (click here to see this wiki article). In the work of Panzer Annales typographici ab artis inventae origine ad annvm MD, Panzer, Georg Wolfgang Franz, 1729-1805, we see numerous references to Denis Suppl. To finish this page I show below a rough translation of item 117 in de Bure's main catalogue Bibliographie instructive, this is the Speculum that we have been investigating, that was purchased by Prefond, and that is now in the Bodleian Library as S-268 (Douce 205) |

| T H E O L O G I E. page 127 number I 17. SPECULUM HUMANAE SALVATIOIS, Editio primae vetustatis, Tentamis Artis impressoriae, abscond loco & anno. Small in fol. This work is neither less curious nor less singular than the preceding ones; and its rarity is known from a longer hand. It is a small folio consisting of 63 leaves marked and printed on one side only, in which are represented the mysteries of our Faith, by 58 stamens, under each of which we notice two columns of Latin rhymes, in letters Gothic. These 58 prints are in the form of vignettes, separated in the middle by a gothic ornament, and loaded with a few words, to make the figures speak, or explain them. Several persons have claimed that the printing of the plates was made before the discovery of the Imprimerie, and that the explanations which are at the bottom of each of them were printed only in the second place. The variety of sentiments on this subject has given rise to several dissertations which have been brought to light, and in which it is easy to learn from all these literary disputes, which are not yet finished. One must find at the beginning of the Volume, and before the 58 prints announced, a sort of Latin Preface, of five leaves, which begins with Latin verses, and which serve to form, so to speak, the title of the work- here they are. Prohemium cujusdam incipit novae compilationis, Cujus nomen & titulus is speculum humanae salvationis. In Paris up to four copies of this famous work are found. The first in the King's Library, the second in the Bibliotheque de Sorbonne, the third in the Library of Celestins; and the last in the cabinet of the President of Cotte, who belonged to the late M. de Boze. In our verification of these copies, we have noticed in the same Volume, differences in the manufacture of characters, which might suggest that they were made with separate parts of two different editions, which would have been collected. The greater part of the explanations which appear under the figures, is printed second, and separately from the body of the print, with characters of cast iron, and movable; but there are pages in which the figures appear to have been carved with the explanations, on one and the same wooden board, which then printed them together. Without deciding on it, we are simply announcing only what we have seen. Another edition of this book is related, and it is also claimed to be ancient. This eddition, which must be very rare, is in the Flemish language, and it is said to exist among the Dutch, who attribute these essays to Laurent Coster of Harlem, and trace the date to the year 1440. We have not seen this last, and we believe that there is no copy in Paris; but we know one in Flemish, which is still very rare. It was printed in Cologne, in 1483, in 4 format. The same character is found in the figures, and its title, which is in the language of the country, is conceived in these terms: Spiegel onser Behoudenisse: Van Culemburch by my Johan Veldener in'tiaer ons heren. M. CCCC. in LXXXIII. Saterdaghi, post Matthai Apostoli. |

|

click here to return to the HOME page. click here to see the INDEX of the 2017 pages. see below links to previous work |

| Even experts are sometimes wrong, before you spend thousands on a book, please do your own research! Just because I say a certain binding can be attributed to le Maitre isn't any kind of guarantee, don't take my word for it, go a step further and get your own proof. In these pages I have provided you with a way of doing just that. |

| Virtual Bookings, created by L. A. Miller | return to the Home page of VIRTUAL BOOKBINDINGS |