| On the previous page I mentioned the fact that Padeloup made the centerpiece armorials, not with a block as was the practice from the previous century, but crafted it by hand using his own small tools. Thus each if his bindings stands out apart from all other decorators as unique if only for this reason. On this page I decided to show proof of my claims, in case you might have doubts that anyone could go to such lengths when a simple all in one block was readily available. |

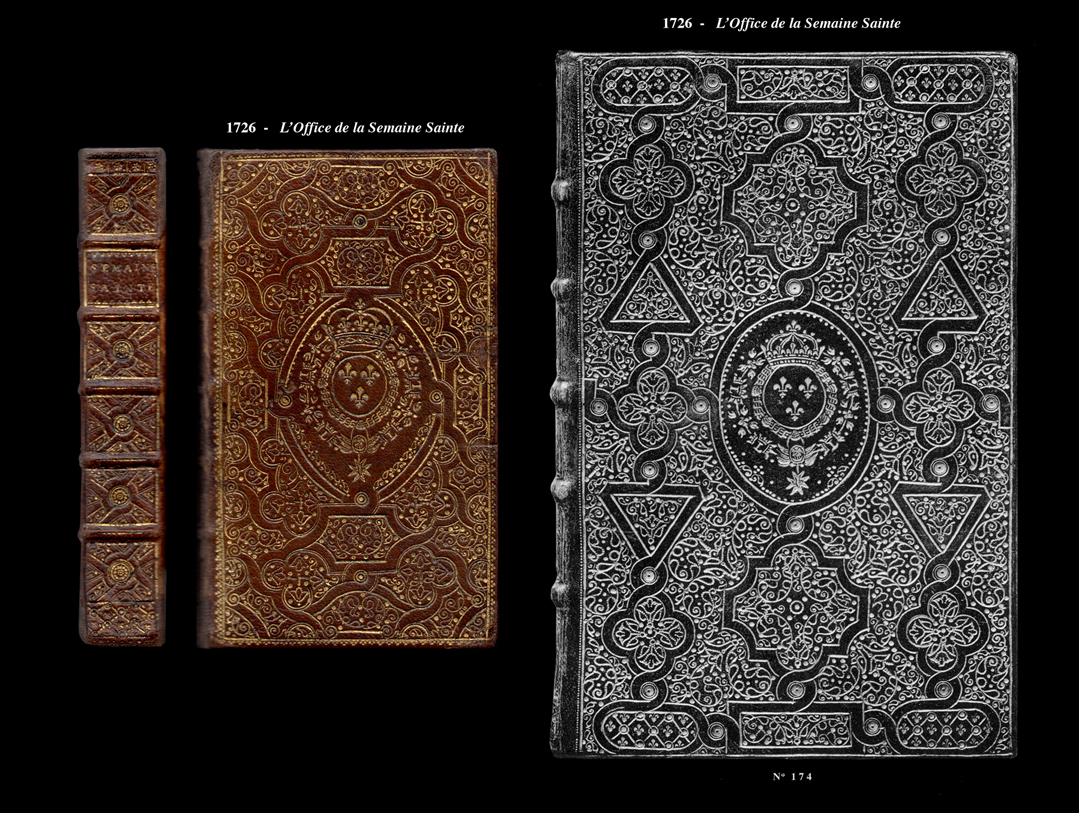

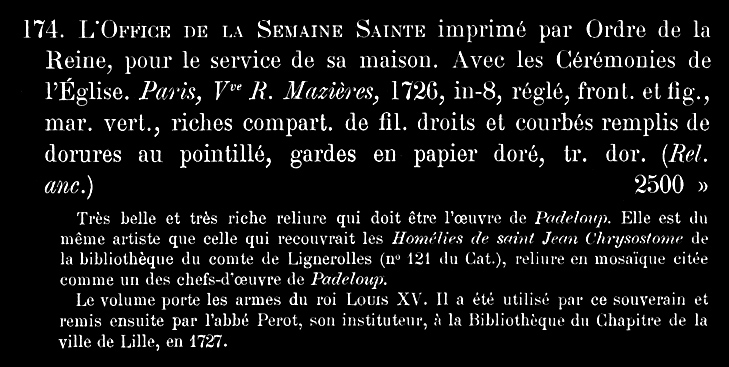

| I have chosen a binding found in a famous Edouard Rahir catalogue: Livres dans de riches reliures des seizime, dix-septime, dix-huitime et dix-neuvime sicles.Paris, D. Morgand, 1910. this is item No. 174 it is another 1726 Office de la Semaine Sainte. Last night I was pondering the problem of knowing if these bindings were really made in the same year as the publication date, as many are not. Here however Rahir solves this problem in his information about this item, stating "Il été utilisé par ce souverain et remis ensuite par l'abbé Perot , son instituteur , à la Bibliothèque du Chapitre de la ville de Lille , en 1727" "It was used by this sovereign (Louis XV) and then returned by the Abbé Perot, his teacher, to the Chapter Library of the city of Lille, in 1727". Google Translation It is a very rough translation, however as I understant this, Louis XV had this book probably in 1726 but it was later given to l'abbe Perot in 1727. This is very good luck to find this information as we can consider this binding by Padeloup was certainly made sometime in 1726 or 1727. We are now going to compare parts of the centerpiece armorials. of these two 1726 Semaine Sainte fanfare bindings by Padeloup. |

| When I was testing these two examples of this medallion, I was thinking that my Rahir 1726 was perhaps out of scale, it seems larger, however when you make the overlay you can see that they are exactly the same size, the Rahir example has some additional embellishment, the core medallion is however the same. In the center of the medallion we see Saint Michel standing on a rock (Mont Saint-Michel) in combat with the serpent, another interpretation says: "The pendant, attached by a double gold chain, represents Saint Michael slaying the devil". |

| In the overlay diagrams we show that the shell (scallop) is separate from the chain. In the upper overlay the shell is not correctly oriented when chain is. In the lower overlay the shell matches, i.e. the upper part matches the part underneath, but in this case the chain does not match. If the shell was part of the chain (attached to the chain) as soon as the upper and lower parts of the shell line up the chain should automatically line up as well, but this does not happen. |

| The outer collar bearing 4 of the monogrammed triple crowned Ls is the support for the cross of the order of the Holly Spirit, Croix de l'ordre du Saint-Esprit. In the overlay we see that the monogrammed letter "L" is the same in both examples, however because we can observe a change in the angularity of one of the examples, this demonstrates that it is a separate item and is not attached to the other surrounding imprints. Note as well that the small flames next to the "L" are oriented differently, One of the examples in our 1726 binding is obviously not pointing in the correct way, this demonstrates that these are separate individual imprints, that Padeloup would have had to apply 32 different times, being careful to orient them correctly each time at a slightly different angle. (sacré Padeloup!) |

| In the overlay of Comparative Diagram 6 we see that these imprints do not match up, this means that each one has been placed individually. These few diagrams are enough to show that these armorial centerpieces were made with small tools and not with the standard large armorial stamp. One can only guess that Padeloup went though this extra work because he enjoyed it. Maybe he was the only one who dared to do it. Fortunately he was older than Louis XV who may not have made a fuss when he saw his armorial looking rather irregular, or maybe when he confronted Padeloup on the subject, his reply was "its rococo!" your majesty. |

|

I do not need to explain these green arrows they point out differences that are obvious when you look for them. The easiest way to show that these armorial centerpieces were made by hand bit by bit is just this diagram that shows the imprints from both sides of this binding. The positions of the imprints are all slightly different, some more than others. Think about this, Padeloup would have had to remember quite exactly what he did on the other board for these tiny imprints to match up at all. Some years ago when I was in my Padeloup period, I remember thinking that the style of this 1726 example No.174 from Rahir's catalogue was a more modern evolution in Padeloup's fanfare designs. If I was to guess I would say that our small Padeloup is of the older style, which would suggest that it must have been made before No.174! Then there is the 1728 binding shown on the previous page, that again would seem the older style, so its not impossible that the small fanfare binding was in fact, made after 1726. The oval shape of the enclosure for the armorial centerpiece, that is present in both the 1726 and 1728 could also suggest a later date. |

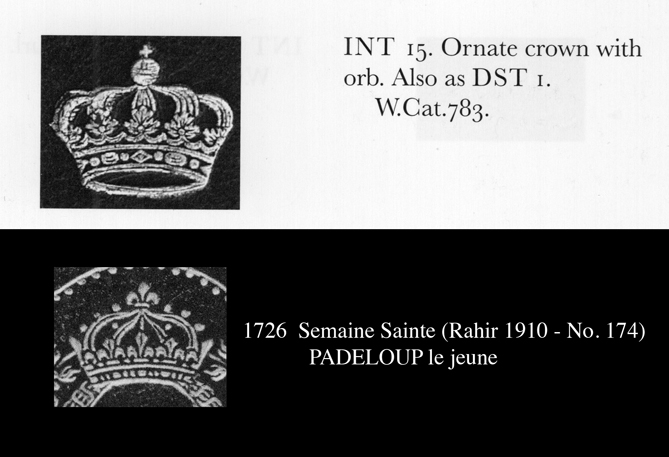

| Padeloup must have decided that an "all on one" stamp for the crown part of the armorial centerpiece of the Rahir No. 174, might be a better option as the crown on our smaller fanfare binding looks almost unfinished and seems too large (comparatively). |

|

I want to add here, some information that I discovered while searching for everything Padeloup on the internet. One well recorded fact is that he died shortly before 5 p.m. on Thursday, September 7, 1758. He was born on December 22nd 1685, and was married more than once but the last time was on April 20, 1751, he married, (at the age of sixty-five years and four months), Claude Perrot, who was only nineteen and a half years old. This means he only had about seven years left to live, yet it is said that he had several children with Claude (April 12, 1752, October 13, 1753, August 13, 1755, January 9, 1757, January 9, 1758, May 27, 1759). Now this must be some kind of a world record for man in his late 60… especially at a time when the average life span for someone living in 18th century France was only about 30! Let us do a simple calculation, if these dates are correct and that the last child was born on May 27th 1759… I went to

researchmaniacs.com to find out when this child could have been conceived https://researchmaniacs.com/Calculate/Conceived/1759/When-was-I-conceived-if-I-was-born-May-27-1759.html Oddly enough, the results were exactly what I was expecting: "According to our calculation, we estimate that your date of conception was on Sunday, September 3, 1758. It is not an exact science and the date of conception may be a few days before or after the date above. We list our best estimate range of dates below. Thursday, August 31, 1758 Friday, September 1, 1758 Saturday, September 2, 1758 Sunday, September 3, 1758 Monday, September 4, 1758 Tuesday, September 5, 1758 Wednesday, September 6, 1758 Thursday, September 7, 1758" It could be that dear old Padeloup over did it that day… sacré Padeloup! |

|

click here to return to the HOME page. click here to see the INDEX of the 2017 pages. see below links to previous work |

| Even experts are sometimes wrong, before you spend thousands on a book, please do your own research! Just because I say a certain binding can be attributed to le Maitre isn't any kind of guarantee, don't take my word for it, go a step further and get your own proof. In these pages I have provided you with a way of doing just that. |

| Virtual Bookings, created by L. A. Miller | return to the Home page of VIRTUAL BOOKBINDINGS |